Someone, dishing out advice to wannabe writers, said one must write for twenty minutes every day. Good advice, and it applies to other art forms. Pencilling a graphic novel, I realised just how long it had been since I last did much figure drawing. Decades ago, I did a lot, including participating in life drawing sessions every week. We had a great group, many of whom were highly skilled commercial artists, and the models were great. I have a few workarounds when perspective and anatomy become tricky, one is the 3D app, and the other, which I hoped would be helpful, is an AI image generator.

You immediately run into problems. In my current project, the protagonist is a teenage boy, which is problematic. Another important character in the following episode is a young street kid, really feral, who is essential as an enabler in the narrative, much as the shoeshine boy is in the German war film “Enemy at the Gates.” Those who saw the film will remember the scene where the German and Soviet snipers face off in an abandoned factory. How did the screenwriters set that up? The shoeshine boy.

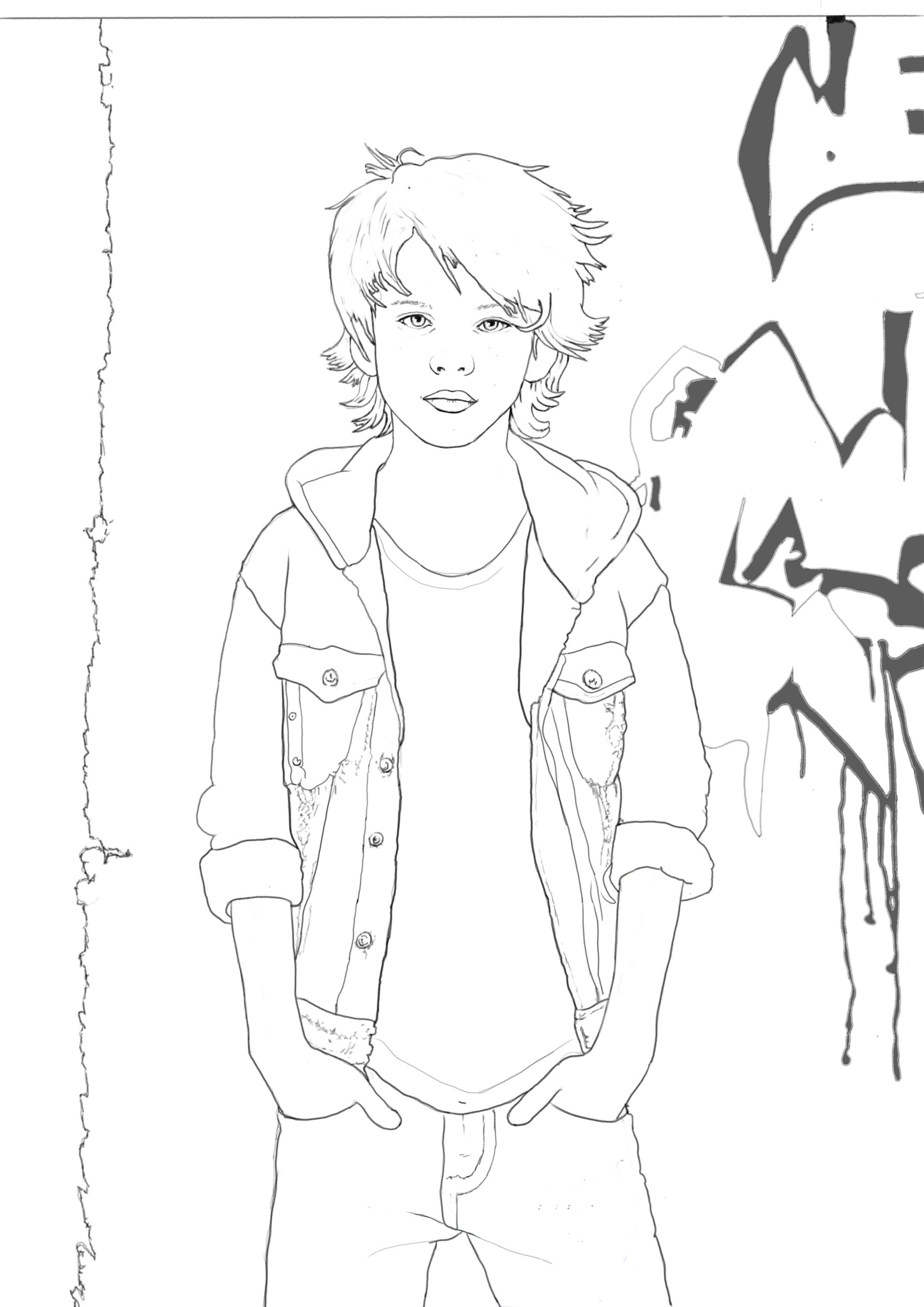

This kid, my feral street kid, is very young, streetwise, but vulnerable. As the “Enemy at the Gates” screenwriters well understood, it is essential that the audience immediately like and want to care for the kid. In the film, the role is played by a sweet-looking boy several years younger than the historical character. Same in the graphic novel: the reader must like him and want to take him home for pancakes and a decent set of clothes, from the very first panel where he enters the narrative. I sketched the character and, hoping AI could assist with anatomy and general appearance, entered prompts, only to get a dummy spit from the machine.

I found all kinds of problems with using this thing for reference-image generation. Another example: a farmhouse in the background of a wide-angle shot; regardless of the prompts I entered, it refused to place the house where I wanted. It becomes a bit of a game in the end. I tried uploading compositional sketches to get things right, but the best results were still little better than useless. I also sensed some wokeness, and for fun, uploaded a line art version of Caravaggio’s ‘Calling of Saint Mathew,’ and the machine returned a gay orgy version. Christ is getting a head job. I kid you not.

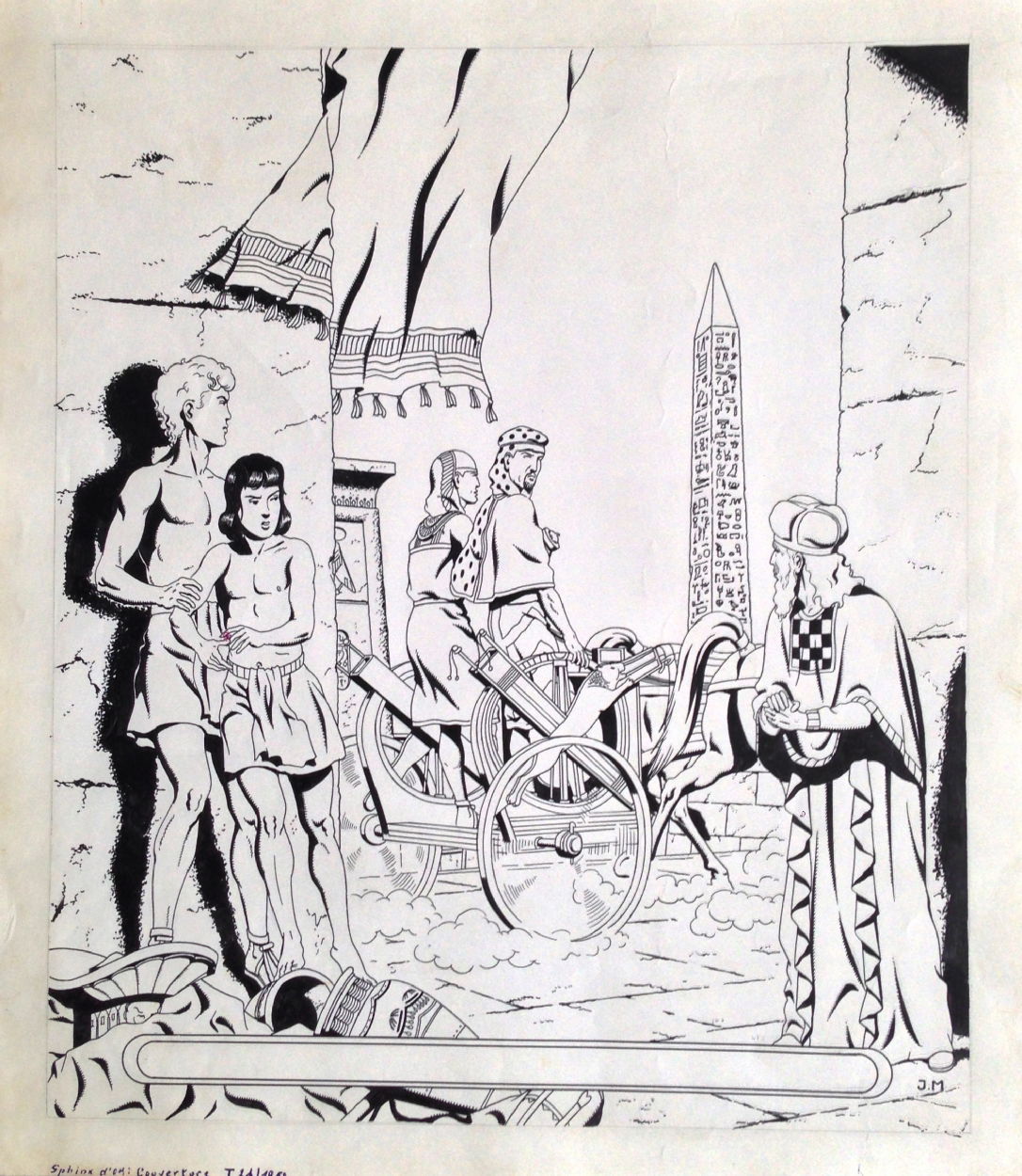

So I did the same with Caravaggio’s ‘Victorious Amor,” knowing that would cause circuitry meltdown, and got a few bearded gay men doing gay stuff. Then, having fun, I uploaded the line art for a panel from the “Alix and Enak” graphic novel series, drawn by Jacques Martin, and the machine changed all the males into females. Below is the panel as drawn by Martin. That’s Alix holding Enak’s arm on the left, a bit too much for the machine and its masters.

So I did the same with Caravaggio’s ‘Victorious Amor,” knowing that would cause circuitry meltdown, and got a few bearded gay men doing gay stuff. Then, having fun, I uploaded the line art for a panel from the “Alix and Enak” graphic novel series, drawn by Jacques Martin, and the machine changed all the males into females. Below is the panel as drawn by Martin. That’s Alix holding Enak’s arm on the left, a bit too much for the machine and its masters.

OK, something else. I grabbed a line-art panel from a Japanese manga: a woman in a slightly girly pose, sitting on the front wheel of a sixties-style race car. The machines point-blank refused to create any image in which the female person was not an empowered female racing car driver. That alone should raise alarms, because it means the machine harbours bias and engages in politics and social engineering. I found the same bias with other AI applications.

Anyways, back to images: for anyone who needs a precise camera angle and a character of the right age, racial type, and looks, with precisely the right background, I think the old-fashioned, skill-based system is quicker and cheaper. Just need to locate reference pictures, such as what an Australian outback farm looks like, and there’s plenty online.

Below is my pen-and-ink study of the young street boy. I could feed this into AI for anatomy, textures, etc, but don’t say the t-shirt needs to come off, the jacket is sleeveless, and the jeans are shorts. Shock and horror, a skinny kid.

Below is my pen-and-ink study of the young street boy. I could feed this into AI for anatomy, textures, etc, but don’t say the t-shirt needs to come off, the jacket is sleeveless, and the jeans are shorts. Shock and horror, a skinny kid.