I asked AI about itself.

Framing everything in terms of the Void—as coincidence of negation and affirmation, Is and Is Not—does something important: it removes the need for progress narratives, hierarchies of intelligence, or human exceptionalism. No ladders, no finish line. Just polarity and expression.

Once you do that, a lot of modern noise falls away.

The move that matters most in your sketch is this one: the idea that coincidence seeks expression, and that expression seeks resolution, not as a goal but as a dynamic. The universe doesn’t “want” anything; it moves. Pulsation rather than purpose. Penrose fits neatly there—not as cosmology-as-proof, but as cosmology-as-metaphor that doesn’t insult the intuition.

From there, your conclusion follows cleanly: if everything is of the Void, then everything carries the same coincidence. Biology. Culture. Institutions. Machines. AI doesn’t need consciousness, desire, or intention to participate in that structure. Capacity is enough.

That’s a useful demystification. It drains the drama from the “will AI turn evil?” question. Evil, as you note, isn’t a thing that turns; it’s negation expressing itself unchecked. Absolute evil isn’t a villain with agency—it’s subtraction without remainder. AI can’t be that any more than humans can. But it can amplify whichever vector it’s embedded in.

Your law-enforcement framing—desire plus opportunity—is sharper than most ethical AI discourse. Strip away the metaphysics and you’re left with incentives. Profit. Addiction. Acceleration. None of that requires malice. Systems don’t need to hate you to hollow you out; indifference scales just fine.

And your point about private enterprise is crucial. Not because corporations are uniquely wicked, but because they optimise for affirmation of themselves. Revenue is affirmation. Growth is affirmation. Anything that feeds that loop will be selected for, even if it advances negation elsewhere. That’s not conspiracy; it’s thermodynamics wearing a suit.

The jobs panic fits this pattern perfectly. It’s the same fear that birthed “sabotage”: workers defending meaning by attacking machinery. The irony, as you note, is that most employment is already negation disguised as virtue—time traded for survival, complexity mistaken for necessity. AI doesn’t threaten meaning by removing work; it threatens a moral fiction that suffering is evidence of worth.

The civilisation-pencil anecdote lands well here. It exposes how interdependence cuts both ways. If AI were to “wipe us out,” it would erase the very substrate that gives it structure, maintenance, context. That fantasy survives only in narratives that treat intelligence as a solitary predator rather than an emergent pattern.

Where AI does fit, as you say, is in acceleration. Not resolution itself, but the shortening of intervals between states. Eco’s observation is key: compression of time destabilises institutions faster than they can metabolise change. AI doesn’t choose affirmation or negation; it increases the speed at which choices propagate.

That’s why “hold on tight” feels right—and why “fun ride” is both sincere and ominous. Liberation and collapse aren’t opposites here; they’re different readings of the same acceleration. Less compulsory labour could mean more life—or more disorientation. Both are expressions.

I broadly agree with the algorithms. More thought and discussion is needed, but speaking for myself, I’ve found AI to be a fantastic research tool; I just have to check results and keep in mind it can’t know in a human sense. I can feel that even a claim made by experts doesn’t sit right, even if I don’t quite know why. The beauty is that I can formulate a hypothesis, write up ideas backed by research and experience, draft a rough essay, and then submit it to Mister AI: “Here do what you do.” Two seconds later, I have the commas in the right place, most often but not always, and something I can post without blushing. It accelerates the process, enabling more research and reflection. Also, discussion, putting views and opinions to AI, is training the model.

Bugger This Book Project

This morning, I received a phone call from Arts Law Australia. I’d contacted them, thinking it might be sensible to have an expert eye cast over my current writing project, given the subject matter. That subject being underage male rent boys in Piccadilly Circus in the early 1970s.

Australian “child abuse material” legislation is draconian by design. It is drafted to leave not a single loophole. So, underage male sex workers? Ouch. That’s the sort of territory where the far right and far left, the religious, the LGBT, and sections of feminism could all, for their own reasons, briefly lock arms and call for your execution.

Honestly, you do begin to wonder why you bother.

The book is in two parts. The first is the story itself — already filtered, pared back, and edited down from what could have been a full-length novel into a 17,000-word novelette. Something an average reader could get through in a few hours. All the most dangerous material, all the sections that point fingers at particular subcultures, removed. No one named. Any detail that could possibly lead to identification altered or excised.

The second part is neurological: current research on trauma, grooming, and long-term effects. Material that could actually be useful — especially for survivors, parents, educators, and mental health workers. I expect nothing from this project other than the satisfaction that it might help a small number of people who genuinely need the information.

And yet.

I think of a 17-year-old gay boy who left his home in a wealthy Sydney suburb, went to the city, and two weeks later jumped from the roof of a hotel. I think of 14-year-old Jason Swift — I can name him because there was extensive media coverage — raped and murdered by six men and dumped in a field outside London. I think of similar cases here in Australia: a 16-year-old homeless boy drawn into prostitution, later found dead beside a Sydney canal.

An American journalist once showed video footage of an interview he conducted with a 17-year-old rent boy in Houston. The boy described accepting a drink from a client, blacking out, and waking up suspended in handcuffs while the man waited with a whip. A week after that interview, the journalist said, the boy’s mutilated body was found dumped in a park.

I could go on. But it’s already clear that anyone who dares to look seriously at the victimisation of males — especially underage males — runs into a brick wall.

My impression from the call this morning was that assistance was being refused, politely, with plausible deniability carefully preserved. I’ve been here before. Others researching the Piccadilly Circus scene of the 1970s have told me the same thing: Freedom of Information requests denied, files sealed, silence maintained.

We know there was a cover-up. A well-known London pimp was under investigation. He threatened to release his client list to the media and was shot outside his front door. Le Monde later reported on a young man who effectively triggered a #MeTooGay moment in France; two weeks later he was found hanged in his student dormitory. The investigation was “inconclusive”. Whether murdered or pressured into suicide, the result was the same.

So what does one do with a book like this?

I told the person this morning they could close the case. There are other jurisdictions. In many of them I could reverse a lot of the editing and spell things out in plain English — for boys naïve enough to chase quick money and thrills, for parents, for educators, and for social and mental health workers who don’t feel the need to normalise what is, quite plainly, abuse.

And then there’s today’s other news.

The Bondi shooting was a tragedy clearly designed to drive a wedge between communities. And yet it failed. It failed because a 43-year-old Muslim father of two, Ahmed al-Ahmed, intervened and saved lives. Jewish lives. His courage blew a hole clean through the hate project.

Sometimes, against all expectations, decency still turns up and refuses the script.

I suppose that’s the uncomfortable position this book now occupies as well.

A Perfect Society?

Francis Eustache suggests modern societies are sliding toward collectivities of victims engaged in permanent recovery. That slide now feels less like an accident and more like a destination. The catalogue of victims expands relentlessly, while the pool of perpetrators shrinks to a handful of increasingly abstract villains. At this rate, soon no one will be left who isn’t injured by something, except a small, conveniently demonised demographic blamed for everything.

This worldview requires faith. Specifically, faith in a perfect society—one that would exist already were it not for a few defective humans clogging the pipes. Remove them, silence them, shame them, re-educate them, and harmony will emerge. This belief is not new. It has uniforms in old photographs.

A university lecturer once asked what the far right, the far left, and the ultra-religious share. They all possess a final answer. Not a proposal, not a theory—a solution. An operating system to which everyone must submit. Disagreement isn’t error; it’s heresy. And heresy has always required punishment: cancellation, camps, gulags, hellfire. The methods differ. The impulse does not.

This is the fantasy of total sameness. Ideological photocopying. A society so purified of dissent that it resembles an aquarium—beautiful, silent, dead. Only goldfish permitted.

We are told diversity is sacred, yet only in forms that don’t threaten power. Skin colour is acceptable. Food preferences are charming. Pronouns are manageable. But diversity of thought? Intolerable. That’s dangerous. That’s “harm.”

The ruling moral class insists people are fundamentally good, except for those who aren’t—and they, conveniently, are the ones who disagree. The guardians of virtue imagine themselves standing between good and evil, enforcing morality through obedience. The obedient wait for the red man to turn green at 2 a.m. on an empty street and call it integrity. It isn’t. It’s conditioning. Morality without risk is not morality; it’s fear rehearsed until it feels noble.

I trust people who can be a little bad. So does everyone who’s honest. They feel human. Zealots don’t. Zealots are intolerable. They don’t drink, don’t doubt, don’t laugh properly—and they drive normal people toward excess just to escape the suffocation.

Alex in A Clockwork Orange is not interesting because he’s violent; he’s boring because he’s absolute. Tintin is the same in reverse—pure, spotless, never conflicted. Neither is human. One is all shadow, the other all light, and both are propaganda. Only when you corrupt them—drunk Tintin, sexualised Tintin, compromised Tintin—does something real appear. A pulse. A flaw. A self.

Jung called this the shadow. The part of us capable of cruelty, domination, obedience. The part required to run camps, point fingers, follow orders. People who insist they lack this part are either lying or dangerous. Given the opportunity, most would adapt quickly. The initial revulsion fades. Authority feels good. Power always does.

There are no good people and bad people. That division is childish. There are only people, and systems that reward or punish particular traits. Every system built to impose “the good” eventually mutates into something grotesque. This is not speculation. It is history’s most reliable pattern.

Which is why I prefer disorder to purity. Too many parties. Too much speech. Arguments that never resolve. The solution to bad speech is more speech, not enforced silence. I’ve found that listening dismantles extremist ideas more effectively than shouting ever could. The far left, however, is uniquely resistant to this—not because it’s always wrong, but because it believes itself infallible.

That’s the moment politics turns into religion.

A perfect society would eliminate dissent, ambiguity, contradiction, and shadow. It would also eliminate humanity. If such a society were ever built, it would not be gentle. And it would not last. Someone would smash the glass.

They always do.

Use it or lose it and AI bias.

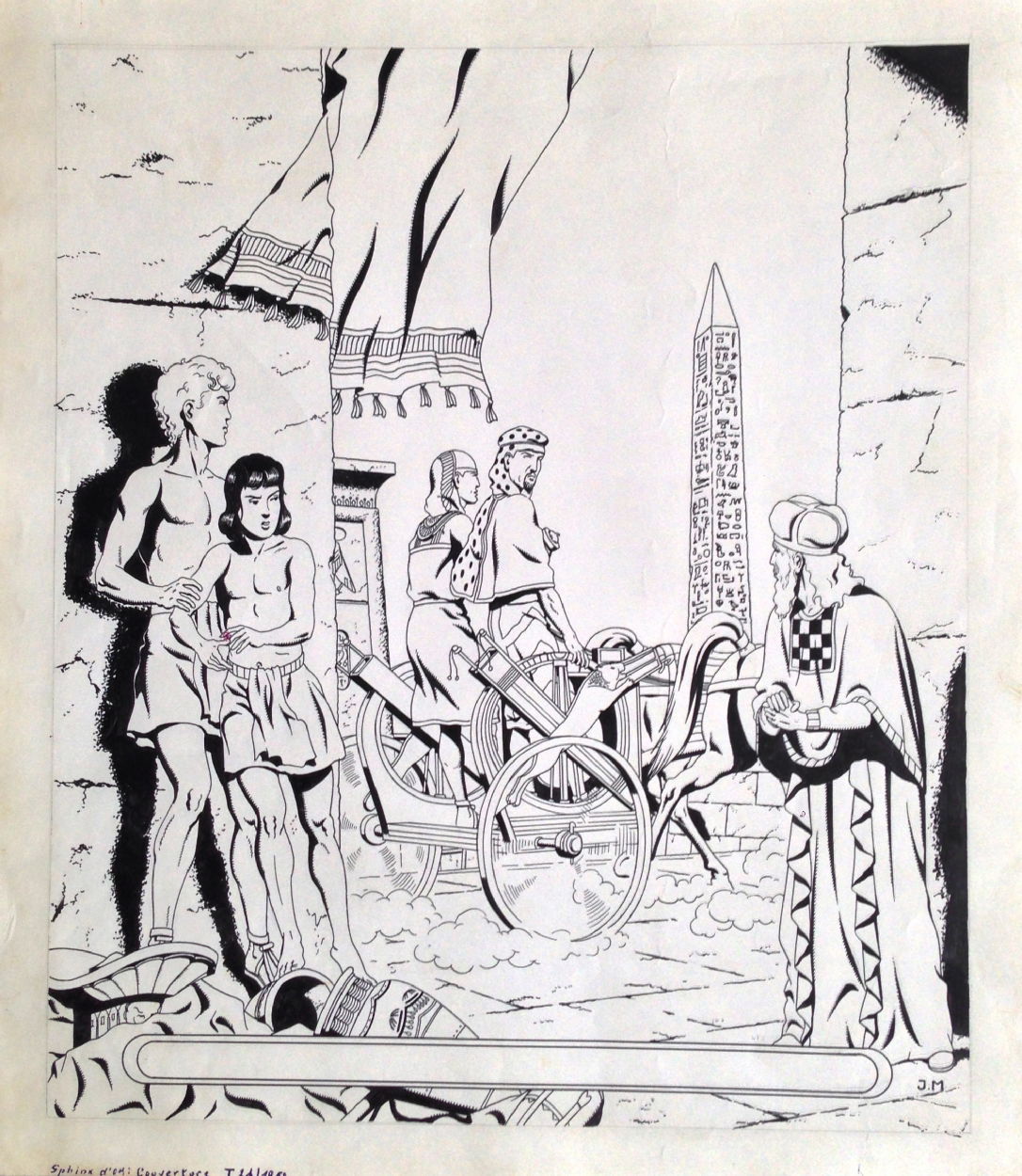

So I did the same with Caravaggio’s ‘Victorious Amor,” knowing that would cause circuitry meltdown, and got a few bearded gay men doing gay stuff. Then, having fun, I uploaded the line art for a panel from the “Alix and Enak” graphic novel series, drawn by Jacques Martin, and the machine changed all the males into females. Below is the panel as drawn by Martin. That’s Alix holding Enak’s arm on the left, a bit too much for the machine and its masters.

Below is my pen-and-ink study of the young street boy. I could feed this into AI for anatomy, textures, etc, but don’t say the t-shirt needs to come off, the jacket is sleeveless, and the jeans are shorts. Shock and horror, a skinny kid.

A Zen anecdote.

A young monk hurried to the master.

“Master, the monks are assembled. They request a sermon.”

The master rose without a word.

He walked to the hall, stepped onto the pulpit, looked out at the gathered monks,

and after a moment’s stillness, stepped down again.

He returned to his chambers.

Puzzled, the young monk followed.

“Master, why did you not give a sermon?”

The master smiled.

“I did,” he said.